One is Remarkably Eclectic

Ivan Lindsay on the story behind the Royal Collection — not only the finest private accumulation of artworks, objets and curios in the world, but also a mirror of the diverse tastes and predilections of every British monarch since Charles I

THE ROYAL COLLECTION has been amassed by kings and queens over the last 500 years and is the largest art collection in private hands. It includes textiles, fans, armour, prints and maps, manuscripts, books, jewellery, sculpture, silver, clocks, ceramics, furniture, watercolours and paintings. It contains over 7,000 paintings, 500,000 prints and 30,000 drawings and watercolours (including 600 by Leonardo da Vinci).

Although a few items can be traced back to Henry VIII and earlier monarchs, the first significant royal collector was Charles I, who was described by Rubens as ‘the greatest amateur of paintings among the princes of the world’. Charles was a second son who never expected the throne.

When his older brother, Henry, Prince of Wales, died of typhoid aged eighteen in 1612, Charles was thrust into the role of heir apparent. Archbishop Laud described Charles as ‘a mild and gracious prince who knew not how to be, or how to be made, great’, while Ralph Dutton observed: ‘In spite of his intelligence… his manner was not helped by his stammer and thick Scottish accent, while in public he was seldom able to make a happy impression.’

England had been isolated from Europe since Philip II had unsuccessfully tried to invade with his armada in 1588. When James I re-established diplomatic relations in 1603 and the English started to travel to the Hapsburg courts of Vienna and Madrid, they realised they had missed out on the southern European renaissance, including artists such as Titian, Raphael, Correggio and Botticelli. Charles believed that if he started a major art collection it would make up for some of his deficiencies and enhance his royal stature.

Charles promptly set off to Madrid with George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, who was described as ‘the handsomest-bodied man in all of England’. Buckingham had been the favourite of Charles’s father and knew how to play the role of courtier. Good-looking and charming, he was also crass, opinionated and a hopeless general who consistently gave Charles misguided advice on foreign policy. He did, however, share Charles’s love of art and the two of them collected masterpieces while enjoying a round of balls, theatre, bullfights, fireworks and hunting expeditions.

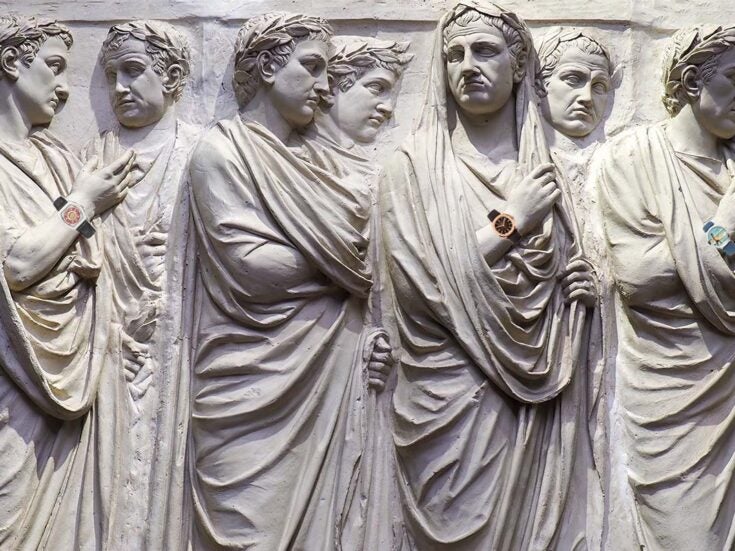

Over the next decade Charles laid the foundations of the Royal Collection, buying masterpieces by Raphael, Leonardo, Tintoretto, Titian, Correggio, Mantegna, Raphael and Gianbologna. He also patronised contemporary artists such as Rubens and van Dyck. Charles frequently agreed one price and then, after taking delivery, paid a lower price that often bankrupted the dealers. In 1627 he agreed to pay £28,000 for the outstanding collection of the Gonzagas of Mantua, but only paid £18,000 on delivery. The shortfall of £10,000 was a significant sum when a junior infantry officer earned £15 a year, and it bankrupted the financier, Daniel Nys, and the dealer, Filippo Burlamachi.

AFTER CHARLES WAS beheaded in 1649, the Rump Parliament, under the direction of Oliver Cromwell, decided to sell off his art collection to raise money for his debtors and to re-equip the navy. Cromwell believed that Charles had identified his reign and royal authority so closely with his art collection that allowing normal people to buy the art would weaken the concept of royalty.

The trustees had difficulty with valuations as Charles had concealed all his paperwork, but sales started shortly afterwards in a complicated story of deception, betrayal, double dealing, switching allegiances, fraud and theft. The demise of Charles and his court allowed the other leading buyers in Europe, such as Philip II, Cardinal Mazarin and Archduke Leopold William, to acquire masterpieces that today remain in the museums of Europe.

The dealers, agents and speculators who participated in these sales made fortunes and the modern art market was born. Colonel John Hutchinson, a close ally of Cromwell who had successfully defended Nottingham Castle during the war, paid £600 for Titian’s voluptuous Pardo Venus, which had been acquired by Charles in 1623 at the Spanish Court. Three years later Hutchinson sold the painting for £7,000 to Cardinal Mazarin, and today it hangs in the Louvre.

This was one of the last sales before Cromwell was appointed Lord Protector (having reluctantly turned down the crown). He immediately halted the sale and reserved the remaining items for his two main palaces at Whitehall and Hampton Court. Having railed against the king’s lifestyle and possessions, he apparently saw no contradiction in trying to achieve something similar. After Charles II (1630–85) was invited back as king by the British in 1660 he exhumed Cromwell’s body from Westminster Abbey, decapitated it, and displayed his head on a pole outside Westminster Hall.

Charles forced anyone who possessed any pictures that had belonged to his father return them or face death, and also started cautiously buying again. It is estimated that of Charles I’s 1,400 paintings, around 300 of the greatest masterpieces were lost to European collectors.

Subsequent monarchs kept adding to the collection in line with their own preferences. William III (1650–1702) liked Boulle furniture, and Mary II (1662–94) collected Chinese and Japanese porcelain. Frederick Louis, Prince of Wales (1707–51) acquired a significant collection of French, Flemish and Italian paintings, and George III (1738–1820) acquired the art collection of the British consul in Venice, Joseph Smith, which included 52 Canalettos and a famous library. George III also patronised contemporary artists such as Ramsay, West, Zoffany, Gainsborough and Stubbs.

George IV (1762–1830) added jewellery, porcelain and sculpture. Queen Victoria (1819–1901) acquired over 1,000 paintings of mixed quality, and her Prince Albert (1819–61) bought some outstanding early Renaissance paintings. Edward VII’s (1841–1910) tastes reflected family, the sea, racehorses and shooting, whereas King George V (1865–1936) and Queen Mary (1867–1953) liked gold boxes and Fabergé. Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother (1900–2002) brought together a strong collection of 20th-century art, and the current Queen (born 1926) has filled specific gaps, encouraged catalogues and improved public access.

Today the collection is primarily displayed in Buckingham Palace, Windsor Castle, Kensington Palace and Hampton Court. The main masterpieces, including the Rembrandts and Rubens, are displayed in the gallery at Buckingham Palace, where they are on view for two months each summer for a fee, and the Queen’s Gallery there has revolving exhibitions.

On ownership, the official position is that ‘the Royal Collection is held in trust by the Queen as sovereign for her successors and the nation, and is not owned by her as an individual’. Nobody seems to know quite what this means; it may be deliberately ambiguous. It appears that this arrangement is connected to the agreement made by George III in 1760 that the Crown lands would be managed on behalf of the government, with surplus revenue going to the Treasury. In return, the monarch receives a fixed annual payment from the government today known as the civil list.

MOST OF THE other collections of the former European royal families are on permanent display in national galleries such as the Louvre, Prado, Mauritshuis, Uffizi and Hermitage. The British Royal Collection is unique in that it remains in the original palaces. Some, such as Brian Sewell, the art critic of the London Evening Standard, argue that the collection would be more easily accessible elsewhere: ‘They should be in the National Gallery; that is where they will have the greatest impact.’ The National Gallery contains around 2,000 paintings, around a third of the size of the Royal Collection, which is small compared to most national collections.

Cromwell’s Rump Parliament rapidly came to the conclusion that the Royal Collection belonged to the people before selling it off. Today the same legal ambiguities exist, but the collection, for the time being, stays in situ and it remains a legacy and testament to the taste of the monarchs of Britain over the last 500 years.

Ivan Lindsay is a Spear’s contributing editor

Pictured above, in order, are: Lucian Freud’s self-portrait, presented to the Queen in 1996; Hogarth’s portrait of David Garrick and his wife (1757) and a Fabergé’s Mosaic Egg (1914), bought by George V in 1933.

The Royal Collection © 2012, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. The exhibition ‘Treasures from the Queen’s Palaces’ at the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh runs until 4 November.