A new Swedish technology is revolutionising the way we live, and sleep, writes Rasika Sittamparam

Mrs Thatcher did it for four hours a night, Richard Branson for six and Donald Trump (by his own account, at least) does it for three.

There is bravado among entrepreneurs, executives and politicians about boasting how little they sleep. This means, of course, that the sleep has to be of the best quality — no sheet-strewn tossing and turning — even as the latest light source to infect our lives, smartphones, stops us nodding off and staying nodded.

But HNWs who rush to beat the clock fail to understand the way their bodies tick: smartphones and laptops by our beds expose our pupils to excessive artificial light, tricking our body clock into thinking it is daytime.

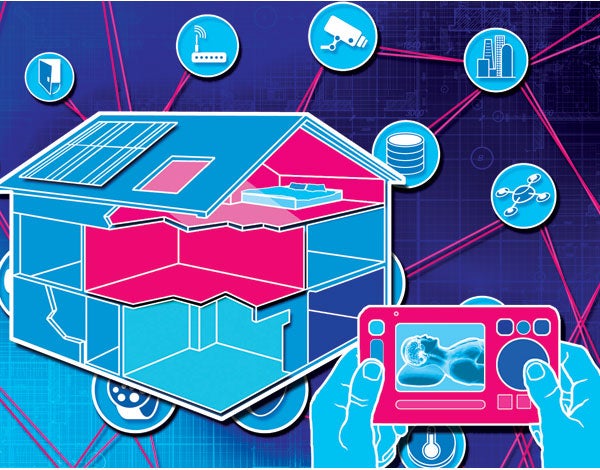

We sleep less as a result and wake up not only to a grumpy start, but a less productive and an unhealthy one as well: there is strong evidence linking insufficient sleep to heart disease and obesity. That’s why HNWs will soon be able to have their architects design smart homes to protect them from their smartphones.

Dr Mark Rea, the director at the US-based Lighting Research Center who spearheads the Healthy Home project in conjunction with the Swedish Energy Agency, describes the effect that light has on the body clock, also known as our circadian rhythm:

‘Imagine flying from England to New York City or vice versa: it takes a while for your biological clock to catch up with the new time, giving you a jetlag — this is driven by the light/dark cycle, the amount of light you are exposed to.’

Artificial lighting indoors can also produce this effect when we are exposed to bright lights in the evening.

Dr Satchin Panda, an associate professor from Salk Institute for Biological Studies in California, runs the Panda Lab, which studies biological clock mechanisms in mammals.

He says light’s effect on the body clock is mediated by a light-sensitive protein in the retina called melanopsin.

Connected via nerve fibres to the hypothalamus in the brain, it sends signals upon receiving intense light stimulus (a few hundred lux, the brightness of fluorescent light) through the pupil, suppressing production of the hormone melatonin, which helps us sleep.

‘A lot of light at night suppresses melatonin production, which explains why we cannot sleep in a lighted room,’ Dr Panda says. ‘A visit to the supermarket at night-time can cause the very bright artificial light indoors to suppress melatonin for a long time.’

In a sense, your body is being tricked into thinking it’s daytime — at night. Contrarily, Panda says being in dim lighting during the day can also affect your biological clock and drain productivity at work.

‘If you walk around with a luxmeter [a sensor that measures light intensity], you will find out that many indoor environments are relatively dark. We need a few hundred lux to activate our biological clock, but we barely have 100 lux of light in many offices and homes.’

The Healthy Home project aims to mitigate light’s influence on the biological clock by automatically reducing bright ‘circadian illumination’ (the light affecting our biological clock) in the evening, but leaving enough light to perform daily tasks.

A 5p-sized wireless sensor, attached to part of the clothing closest to the head, records the amount of light the pupil receives at any time.

The data is then transferred to your smartphone, which operates a programme that recognises you, writes a ‘light prescription’ based on the level of light exposure you’ve received so far and changes the surrounding brightness in your home.

‘We look at iPads and watch TV in the evening,’ says Rea, ‘and the technology would tell you whether that’s a problem or not and how long can you do it without affecting your sleep.’

Rea believes the findings may have broad implications for health by enhancing performance, improving the heart and reducing risk of diseases such diabetes and breast cancer:

‘We live in a culture of chemistry and pills; we think that’s what it takes to be healthy. But if you end up with a regular 24-hour light and dark cycle, you get a profound outcome. It isn’t just baloney — this is such an important part of biology that we’ve ignored for centuries.’

He says the technology can also function as a soundless alarm clock: by telling the phone when you want to wake up, it can then work out the best light exposure to wake you naturally at the desired time.

The prescription will be written every day while you are sleeping and sent out the next morning with a ‘recipe’, perhaps suggesting you get less light that morning and more in the afternoon.

In the future, he says, the programme could also transcend home space to offices and other indoor environments we encounter every day. ‘In theory,’ he says, ‘the technology would recognise you and light up no matter where you go.’

The technological development leg of the project is nearing completion. Then the Lighting Research Center will collaborate with manufacturers around the world and real estate developers in Sweden who are looking to embrace the technology and move away from old-fashioned ‘light architecture’.

Rea envisions a ‘paradigm change’ will be possible by December 2017.

The Healthy Home project is an example of a broader shift in the way architects perceive and apply scientific data.

Stephane Hof, an architect and the founder of Hoffice, loves the challenge of the area: ‘The complexity of today… could be the normality of tomorrow. In architecture, we are at the beginning of understanding the information from research which is even more accessible today.’

Federico Favero, an industrial design specialist at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, says architects need to be patient with the length of scientific process: ‘The construction process is so quick and is driven by demand. However, research doesn’t really match with this speed — it is a pity when the moment evidence is truly consolidated is the time a project has already been completed.’

Another architect, Frederick Marks, has founded the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture in an effort to encourage discussion between architects and scientists to envision buildings that would improve health and wellbeing.

‘Design, as a process, is based on intuition; that is going to continue,’ he says. ‘But what we have now is a chance to confirm what the intuition is saying. When an architect goes to a client and backs up design with scientific data, it will be a clear benefit to the profession.’

What is clear is that even if health-enhancing technology for the home is still rudimentary, HNWs will soon be seizing on the architecture of wellness to improve their performance at home and in the office.

Rasika Sittamparam is a researcher and science & tech writer at Spear’s