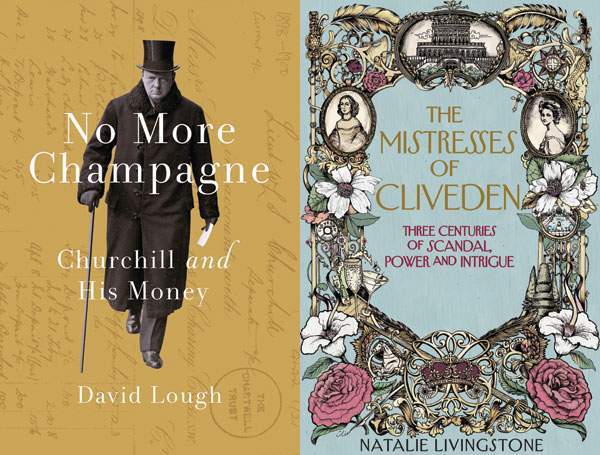

Christopher Silvester on Churchill’s spend, spend, spend lifestyle and Mark Le Fanu on Cliveden’s glamorous, scandalous châtelaines

No More Champagne

David Lough

When it came to money, Winston Churchill was blessed with good luck and cursed with bad habits. In 1921 the death of a cousin in a railway collision in Wales meant that he inherited a landed estate worth £90,000, which generated an annual income of £3,700. Suddenly, he and his wife could afford to pay their bills.

‘I can’t describe the blessed feeling of relief that we need never never be worried about money again (except thro’ our own fault of course!),’ Clementine Churchill told her husband.

‘It is like floating in a bath of cream.’ A couple of days later,

she asked him in a letter: ‘Please may I have a little more money now that you are what the French call a “rentier”?’

Newly wealthy, Churchill managed to squander this fortune within a decade, partly through the cost of converting his country home, Chartwell, and partly through losses in the 1929 Wall Street Crash.

Obliged to resign from the Conservative front bench, he resolved to write his way out of trouble, and indeed he made good from a combination of vigorous journalism and historical books that attracted hefty advances from a publisher in the United States. Nonetheless, his spending increased accordingly and debts soon accumulated.

Churchill had early on been introduced to the spendthrift ways that he indulged as an adult, even once borrowing money from his nanny. His father, Lord Randolph Churchill, once warned him that ‘if you are not more careful should you get into the army six months of it will see you in the Bankruptcy Court’.

His mother, Jennie Jerome, was a beautiful American heiress, and when she married Lord Randolph, a younger son of the Duke of Marlborough, she was allowed to control half her dowry. Lord Randolph mistakenly assured his father that Jennie ‘has a sacred, and I should almost say, insane horror of buying anything she cannot pay for’. As David Lough wittily observes, this ‘was a monumental misjudgement, a hint of which lay in the 25 gowns from leading Parisian couturiers that made up Jennie’s trousseau’.

If Jennie’s vice was buying dresses, Winston’s, once he joined the army, was polo ponies — his father, by then deceased, had shown immense foresight. After Lord Randolph’s death, Jennie and Winston and Winston’s younger brother Jack had to live off the capital he had bequeathed them in the form of South African mining shares. The family finances remained perilous for years, long after Churchill began making money from his journalism and started drawing an MP’s salary.

As the years went by, his vices changed. He bought so much Perrier-Jouët champagne that upon his death the company produced special bottles with a black band of mourning. ‘No more champagne is to be bought,’ he wrote in a 1926 memo to his wife. ‘Cigars must be reduced to four a day.’ Such self-denial was fleeting.

After World War I, when income and super-tax rates rose above 50 per cent, Churchill found that the taxman was his constant adversary, though he used ‘the power of his public position’ shamelessly: ‘Twice while chancellor of the exchequer, for example, Churchill summoned to his aid the chairman of the Inland Revenue, a government agency for which as chancellor he was politically responsible.’

In 1938 fortune smiled on him again when his young aide Brendan Bracken persuaded Sir Henry Strakosch, an Austrian émigré in possession of a South African mining business, with whom Bracken co-owned The Economist, to bail Churchill out by buying £18,000-worth of Vickers da Costa shares (almost a million pounds in today’s money) on which the politician faced a margin call. Strakosch, who admired Churchill’s political courage, was happy to help.

A couple of years later, soon after he took office as prime minister, Churchill needed a second Strakosch bailout so that he could pay bills from his shirt-makers, watch-repairers and wine merchants, as well as his tax and the interest on his bank overdraft.

He made the equivalent of £4 million in today’s money during World War II from selling film rights to his books, but after the war, with income tax reaching 97.5 per cent, he insisted that revenue from his memoirs and other writings be paid as a capital receipt. It was not until 30 years after his death that the duty on his estate was finally settled, once Cambridge University had acquired all his private papers for £12.5 million — with a grant from the National Lottery Fund.

Churchill has hardly been deprived of biographical attention, but Lough, a former private banker, has produced a fascinating and fresh study of the man, of whom he says he has ‘never encountered risk-taking on Churchill’s scale during my career of advising people about their finances’.

The Mistresses of Cliveden

Natalie Livingstone

Cliveden is one of England’s most famous stately homes — though ‘notorious’ is probably the word that more aptly springs to mind.

An imposing neo-Italianate building situated on the upper Thames at Taplow in Buckinghamshire (architect of the present 1851 construction:

Sir Charles Barry, designer of the Houses of Parliament), it served as headquarters during the 1930s, when it was owned by the Astor family, for a group of aristocratic appeasers of Hitler’s Germany known as the Cliveden Set. Later, during the 1960s, the mansion’s spacious grounds, swimming pool and hideaway cottage became the theatre of an almighty sex scandal known to the public as the Profumo Affair, which rocked the Conservative government of the day.

Yet actually its history is far deeper and, one could almost say, more interesting than this. In the 350 or so years since its original foundation, and through diverse changes of ownership, its corridors and drawing rooms have witnessed the comings and goings of major representatives of the nation’s political elite.

Natalie Livingstone, whose first book this is, has had the clever idea of recounting the story of the house through the stories of its various mistresses: she has been lucky to discover that they were on the whole powerful women in their own right — more powerful, in several cases, than their consorts.

The word ‘mistress’, of course, in English has more than one meaning. It means châtelaine and it means — well, ‘mistress’.

In the early years of the house’s history the latter connotation of adultery was very much to the fore. George Villiers, second Duke of Buckingham, built the first version of the house in 1678 as a present for his principal girlfriend, Anna Maria Brudenell, Countess of Shrewsbury, after killing her husband in a duel.

(I didn’t know that duels in those days involved the seconds as well as the protagonists pitching in; in this particular encounter six men were fighting, two of whom, including Shrewsbury, ended the day mortally wounded.)

Buckingham in the event died heirless. The next châtelaine of Cliveden, Elizabeth Villiers, a distant cousin of the duke, was also a prominent mistress — in this case, of no lesser a person than William III. Though plain and squint-eyed, she was clever and charming: Swift and Pope were among her many literary admirers. During her reign, as Countess of Orkney, the house was reshaped by Thomas Archer, one of the major baroque architects, and flourished, like Chatsworth, as a bolthole for Whig Party intrigue.

More intrigue followed in the 18th century when Cliveden was leased from the Orkney heirs by Crown Prince Frederick, son of George II, and his young German wife, Augusta, Princess of Wales. Frederick cordially loathed his stuffy and conservative parents (the lack of esteem was mutual), so in due course Cliveden became the base of a sort of unofficial opposition party to the court, centred around a number of the most influential political figures of the day: Temple, Cobham, Bolingbroke, the Grenville brothers, as well as the future prime minister William Pitt.

It was under Augusta’s aegis that, in 1740, Thomas Arne’s patriotic masque Alfred was premiered in Cliveden’s beautiful gardens bordering the Thames, ending as it does with the rousing anthem Rule, Britannia! — an ‘instant hit’, according to Livingstone. (Wagner was to claim that the first eight notes of the chorus ‘embodied the whole character of the British nation’.)

Alas, those heady days of oppositional idealism were all too brief: Frederick died before he could inherit the kingdom. Augusta made up with her parents-in-law and Cliveden sank into a sort of melancholy gothic decay, culminating in a fire that destroyed the central block of the mansion in 1795.

That was to be the first of two catastrophic blazes in the house’s chequered history. The second occurred in 1850, when the freshly rebuilt mansion had just come into the possession of the then richest woman in England (besides Queen Victoria, who happened to be her best friend): Harriet, Duchess of Sutherland.

She is one of the strongest characters in Livingstone’s narrative, a vigorous reformer and leading light of the anti-slavery movement. As well as being brave, she was rich. We learn that she and her husband owned six other houses up and down the land, but that didn’t stop her immediately commissioning Barry to design a new version of Cliveden to rise from the ashes, grander and more beautiful than ever.

Should anyone ever own seven homes? Spear’s readers will have their own opinion on this matter. Karl Marx, unsurprisingly, had little time for the duchess and her philanthropic endeavours: her husband the duke, after all, had been responsible, under the guise of scientific land improvement, for turfing out thousands of tenant farmers from the couple’s vast northern Scottish estates.

It is a test for Livingstone to acknowledge this awkward historical fact without glossing over its moral implications — a test that she passes with honour.

That leaves one final châtelaine of prominence: the redoubtable American-born campaigner Nancy Astor, first ever female MP. An eccentric of inordinate conviction, Nancy campaigned for women’s causes, but also for Christian Science, teetotalism and the appeasing of Hitler’s Germany. She was a ferocious antisemite, and not very kind to her children (indeed, she loathed sex so much it is odd that she had any).

In short, it is not difficult to rather dislike this person, though in the end it is possible to pity her — and even, grudgingly, to admire her. Her son Bill, at any event, more than made up for her prudishness. This was the Lord Astor about whom Mandy Rice-Davies so memorably remarked (when, at the height of the Profumo affair, he denied having slept with her): ‘Well, he would say that, wouldn’t he?’

The Mistresses of Cliveden has been beautifully produced by Hutchinson, with fine illustrations. Natalie Livingstone (aided, so the acknowledgements tell us, by no fewer than four researchers — how’s that for a first venture into print!) has done an excellent job in bringing to life the house and its denizens. Through marriage to the present leaseholder (Cliveden is now a luxury hotel, rented from the National Trust), she herself is the latest châtelaine. This is family history that is also deep social history — and actually the history of our nation.