Anthony Haden-Guest hails the appointment of Jeffrey Deitch — veteran gallerist and canny operator — as director of LA’s Museum of Contemporary Art

ART BASEL MIAMI BEACH is the art world’s party central, and the Jeffrey Deitch party is always dutifully referenced in media coverage as a prime gotta-be-there. In December the draw was a gig by one of the bands of the moment, LCD Soundsystem, as previous Deitch events in Miami have featured Fischerspooner and Scissor Sisters, and the place was crackling. As the throng swirled past he noted, ‘I may be at a museum, but I still know how to give a party.’

Well, yes, that he does, and this party was for MoCA, Los Angeles’s Museum of Contemporary Art. Deitch is not the first individual to leave the hurly-burly of the art market for the supposedly purer air of the museum uplands, but there had been a tremendous buzz when he closed his two spaces in downtown Manhattan to take up the MoCA directorship. Jerry Saltz, New York magazine’s trenchant art critic, described it as ‘a game-changer’. It is. In certain regards Jeffrey Deitch is as significant an art-world figure as the dealer who is in many regards his polar opposite, Larry Gagosian.

The look hinted at the story. Deitch was as trimly be-suited in exuberant Miami as in the North East. It’s a look that must have seemed a tad conservative even when he was a banker, but in the context of the radical art world it seems as subversive as a Magritte bowler hat. It’s a look the kid from Connecticut adopted early.

‘He was fascinated by the underworld and sexual freedoms,’ says Marcia Resnick, an early New York friend who would become one of the great photographers of the punk era. ‘His fascination with that led to us going to a lot of different underground-type clubs, including rock-and-roll clubs — anything underground, anything behind the scenes. But he was dressing very formally; he stuck out like a sore thumb. He was always so unusual; he was so straight.’

There was nothing accidental about Deitch’s progress from John Weber’s hardcore Conceptual gallery, via an MBA, to Citibank, where Deitch was on the art advisory side for eight years and ended up as a vice-president. In 1988 he left to set up as a private art consultancy, Jeffrey Deitch Inc, based in Trump Tower. Art advisers had long existed, of course, but Deitch was one of the first to professionalise it and was soon an established figure within it.

His timing was in one regard unlucky, with the art world heading into the slump of 1990. Had he seen it coming, I asked shortly after he opened his gallery in 1996?

‘I am a conservative, cautious person,’ Deitch told me. ‘When I left Citibank, a number of people said, “We’ll give you money to buy! Just tell us and we’ll transfer the money.” Somehow I had this instinct that it was not the right thing to do. I did it on a moderate level with some friends; I did some things I regret, luckily on a moderate scale. But if I hadn’t somehow had an instinct not to plunge into this, I would have been completely bankrupt.’

In the early Nineties, art slump or no, Deitch put together two innovative shows for the Greek collector Dakis Joannou: Artificial Nature and Post-Human. He opened his gallery, Deitch Projects, on Wooster St in 1996 with a show by the performance artist Vanessa Beecroft, who was using her signature material: young blonde models, extremely lightly dressed and posed immobile. Artists he soon showed included Japan’s Mariko Mori (luminous sci-fi-inflected photographs) and Cecily Brown, his first actual painter. As this roster suggests, Deitch Projects played a part in enabling a surge of female artists.

DEITCH ONCE TOLD me that he regarded the loss of Cecily Brown to Gagosian as his biggest career reverse. He had others. He and a couple of European gallerists had formed a consortium to back Jeff Koons in the fabrication of his Celebration series of sculptures. The artist ran up such mighty cost overruns that Deitch was forced to sell half his gallery to Sotheby’s and was made a vice-president. His fellow dealers, their war with the auction houses heating up, were aghast, and Deitch ProjectWWs was promptly dumped from such art fairs as Art Basel. But he clambered back and dissolved the partnership with Sotheby’s in 2001, and the extraordinary journey of Deitch Projects continued.

The worst that most artists will say of Deitch is that many of them will feature in a knock-your-eye-out show but that’s it, and that for most there’s no after-care programme. Well, the answer is implicit in the name Deitch Projects. It wasn’t a white box, with a roster of gallery artists getting a show every couple of years, but a project space — or two project spaces rather, after he opened down from Wooster on Grand — and the project, much of which was supported by the collection-building and dealing in the secondary market in the upstairs office, was to show the freshest art being made.

Those who showed with Deitch — and ethics demand that I reveal that he showed my cartoons a few years back — included Jonathan Borofsky, a sculptor with such a visceral distaste for the plurality of art dealers that he mostly restricts himself to public art; Oleg Kulik, a Muscovite performance artist who spent the length of the show on all fours in a cage, naked apart from a studded collar and barking at gallery-goers with convincing ferocity; and Kehinde Wiley, who makes baroque paintings of hiphop stars. But certainly the leitmotif of Deitch Projects was an exploration of the growths and the undergrowth of the culture, and the more exotic they were, the happier the gallerist was.

Deitch was showing street art, for instance, long before Banksy brought it to the auction floor, and he gave an art context to performers like Kembra Pfahler, lead singer of the Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black. It was there that a group of artists put up a skateboard rink, and it was there that Dan Colen, the late Dash Snow and a bevy of young artists made their ‘Nest’, a mess of shredded-up telephone directories, wine, pee and the like, which turned the gallery into a convincing simulacrum of a deranged anarchists’ squat.

DEITCH PROJECTS, IN short, was not — in its public spaces at least — part of that huge art world which is in the business of delivering goods to collectors. It seems to have been this difference, perhaps along with the existence of his network of collectors and supporters, that made him seem a good fit to the powers-that-be at MoCA. ‘It doesn’t stop,’ he once told me. ‘The art world continues to go into new phases. I was just thinking about that today when I was reading things in the news about the entertainment business — how just overnight it transforms. Well, the art business has become that way, too. Overnight there’s something new that just changes everything.’

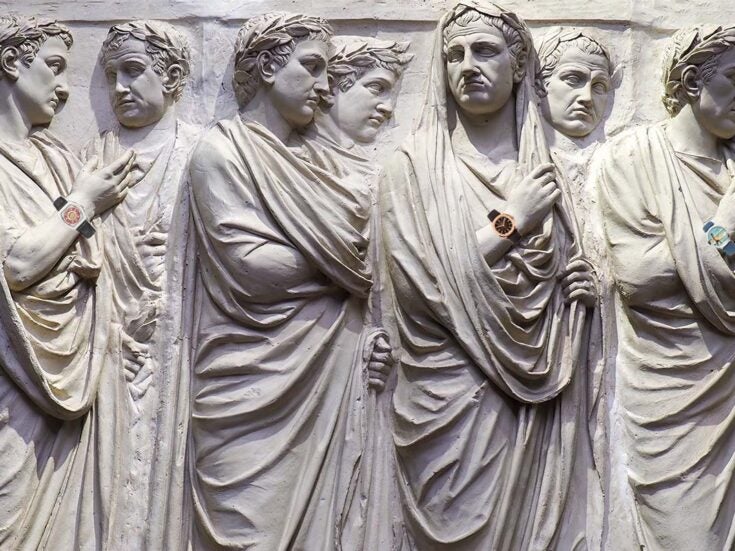

This referencing of the entertainment business is very much to the point. Yes, the art economy is supported at its upper levels by a core of few hundred speculator/collectors, but it has become part of the haute entertainment culture, too. MoCA’s 30th-birthday celebratory dinner last year was orchestrated as an art piece by the Italian artist Francesco Vezzoli, who organised performances by Lady Gaga and some dancers from the Bolshoi. Damien Hirst contributed a customised piano, which was duly auctioned for $450,000.

This, of course, was the art world that Deitch Projects effectively foresaw. Yes, there will be hiccups. There was indeed one already when the Italian street artist Blu painted a mural of military coffins and dollar bills on a museum wall facing the Veterans Hospital. The wall was promptly whitewashed. There was much incandescent commentary in the blogosphere and I was reminded of the seizure by the Metropolitan Police of Richard Prince’s Spiritual America from Pop Life at the Tate Modern. That didn’t change anything either. The art world is changing. As it does.

Photography by Brian Forrest