Diaghilev was no simple showman: working with the best composers and visual artists of his day, he took dance into the twentieth century, says Stephen Hill

THE FIRST THREE decades of twentieth century dance were overshadowed by one man, Sergei Diaghilev (1872-1929), who was originally inspired by his step-mother’s singing. Enlisting in the St. Petersburg Conservatory of Music in his youth, he played the piano, sang, and studied composition, but he never conducted nor danced. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov even told him he had no talent for music!

When he graduated in 1892, neither he nor his teachers were quite certain what he was, but he became the musical equivalent of a Field Marshall when he took his army, Les Ballets Russes, and descended on Le Theâtre du Châtelet in 1909 and took the City of Light by storm. His foot-soldiers, whom he commanded ‘to take Europe by surprise …,’ were led by the innovative choreographer Mikhail Fokine, and included Vaslav Nijinsky and his sister Bronislava, Tamara Karsavina, and later Serge Lifar and Olga Spesivtceva.

Diaghilev, with his multi-faceted artistic leanings, had veered towards Les Arts Plastiques and Paris was fertile ground: ‘He sits down, screws his eyeglass, and exudes a beneficent cloud of inspiration,’ wrote Vladimir Dulesky, whilst his company pioneered many new choreographies, astonishing sets and costumes that were in themselves works of art, many of which are in this commanding new exhibition at the V&A.

He worked with Georges Braques, Jean Cocteau, André Derain, Max Ernst, Naum Gabo, Fernand Légér, Henri Matisse, Joán Miró, Pablo Picasso and Georges Rouault who are all represented here, along with many other talents. Under the command of the Field Marshall they reinvented ballet, with works such as Le Spectre de la Rose, Schéhérazade, Petrushka, The Firebird, Parade, Le Train Bleu, Les Biches, L’Après-midi d’un Faune and twenty-eight other works, the first of these three choreographed by Fokine and the last, that was to cause more than a little stir, by Nijinsky himself.

If Tchaikovsky was the ballet composer par excellence of the nineteenth century, it was surely Igor Stravinsky for the twentieth, with his compositions for Diaghilev such as Le Sacre du Printemps/The Rite of Spring, Apollo, the Firebird Suite, Orpheus, Pulcinella and others, many of them especially commissioned by Diaghilev.

I was privileged to hear Stravinsky himself conduct The Rite of Spring in London in the late-1960s. Much music for ballet does not stand up without the choreography as music on its own, but not so The Rite of Spring. This is a symphony on its own, requiring a massive orchestra to deliver its own staggering, shattering, sound-splitting crescendos and its joyful and playful passages in the string and wind sections.

It is an evocation of the Russian Spring, when the icy grip of Winter’s snows and frosts and biting winds are broken by the sudden onset of Spring and the accompanying dance rituals and sacrifices. The ice cracks at last and the streams flow again, the winds desist and the birds sing and go-a-nesting, the earth warms and the shoots appear and the nymphs dance.

This incredible dance of transformation takes place in just a few days, such is the force of nature that inspired this revolutionary composition for Neoclassical ballet. And excerpts from this ballet are shown on a giant screen in this exhibition to great effect.

In 1926 Diaghilev sent Serge Lifar to look at exhibitions of Ernst and Miró, but Lifar did not take easily to surrealism. So Diaghilev purchased some paintings by both these avant-garde artists and thus a collection began which would eventually include much of Les Ballets Russes’ designs, sets and drawings for costumes in this exhibition.

The poet Guillaume Apollinaire wrote on seeing Parade, scored by Erik Satie, that ‘Picasso and the choreographer Massine have achieved, for the first time, the alliance between painting and dance’; that was in 1917, during WW1. And the incredible costumes on display in this exhibition have influenced Haute Couture ever since, especially Yves Saint Laurent’s famous 1976 collection.

DIAGHILEV’S FIRST RECORDED meeting with Picasso was not until the Autumn of 1915. Picasso was all about dancers and musicians and choreographers, but one painting stands out from his vast oeuvre, The Three Dancers, painted in 1925; its images straddle many dance form painted in 1925; its images straddle many dance forms, from classical ballet to modern dance and much in-between. No wonder he kept this iconic painting, breathing energy, in his private collection, but which is now on display at the Tate Modern exhibition entitled ‘Dreams and Poetry’.

None knew better than Diaghilev that art has to be subversive, it just has to subvert existing forms and styles. Wasn’t it Marshal McLuhan who said ‘Art is one technology ahead’? On 29 May 1912, early on in the life of his company, Diaghilev raised its profile and a lot more besides with L’Après-midi d’un Faune.

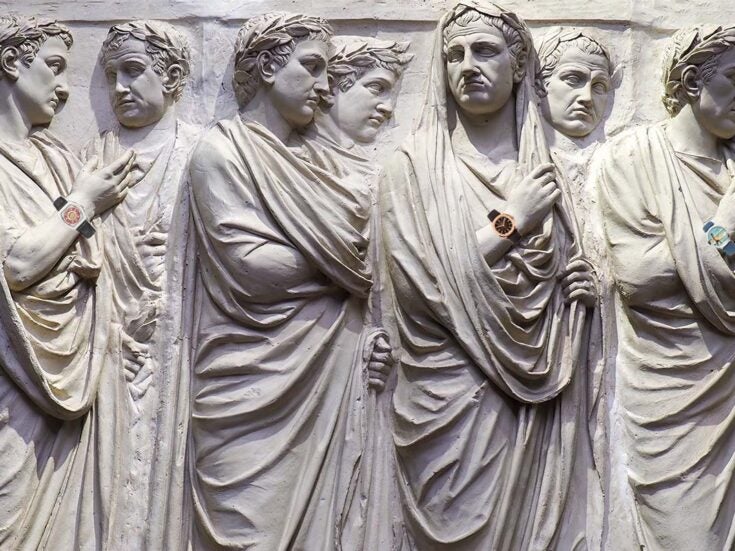

It was revolutionary in many respects, a new form of dancing, a new technique of movement developed by Nijinsky which forsook classical technique of the five positions, but one inspired by the two-dimensional Greek vase and Egyptian frieze painting. Diaghilev had selected an existing score by Debussy, just twelve minutes in duration. There were over one hundred rehearsals for this new style of dance. The storyline was simple:

A faun reclines on a rock playing his pipe, and sucking juice from a bunch of grapes; seven nymphs enter and the faun approaches them. The frightened nymphs dance, and dance away two at a time; the last nymph drops a scarf; the tricked faun picks it up, returns to his rock, lowers the scarf to the ground and lowers himself to the ground too, face downwards onto it, and proceeds to fornicate in postures which were obvious.

The audience erupted. The classical purists were shocked by the new dance technique of Nijinsky. The bourgeois moralists were outraged by the final scene. One half of the audience realized this was new and subversive art and called for an encore, while the other half hissed in derision. The Field Marshall, ever the promoter – ‘Firstly I am a great charlatan, although with added brio; secondly, I am a great charmeur; thirdly, I am a great show-off!’ – lost no time in the general hubbub to order the encore.

And as Nijinsky came to the final act, he did not lie down on the scarf but stood and used it – remember this is 1912, but it is Paris – in an act of simulated fellatio and orgasm. The audience was as scandalized as Diaghilev had intended. Cyril Beaumont the critic, however, on reflection later wrote ‘the movements and poses were performed so quietly, so impersonally, that their true character, with their power to offend, was almost smoothed away’. And Les Ballets Russes never looked back.

What, after all, was the dis’prized faun meant to do with the vanished nymph’s scarf? Blub, and blow his nose into it?