Above: a Henry Darger illustration from his fantasy novel, ‘The Story of the Vivian Girls’, courtesy Andrew Edlin Gallery

It was at a higgledy-piggledy arts event in Manhattan in the early Eighties that I met Joe Coleman, the first Outsider artist I really got to know. A queue of folk in black were tramping upstairs, looking secretive, so my date and I attached ourselves, taking seats near the front. Coleman, the performer, was black-bearded, curiously chunky in the torso area and accompanied by a young woman, who unexpectedly stood on her head. Whereupon Coleman thumped her in the privates. Rather hard. ‘I would have thought that hurt?’ I said to my date, who nodded in stunned agreement. Coleman then popped several white rats into his mouth head first, one at a time, chomped, tossed the leavings aside, and turned his attention to the lumps in his chest, which turned out to be firecrackers, which he lit and exploded.

The audience rushed for the exits as I went into reporter mode, scrabbling to check that the rats were actually headless. Yes! So I got up and said hello to Coleman.

Studio visits followed. It turned out that Coleman’s ferocious performances were just part of his oeuvre. He was and is a stunning painter, working with the exactitude of a Dutch master (say, Hans Memling) to make startling images, usually composed of vignettes structured around a central figure, an organisation like that of an icon. Indeed, Coleman was brought up a Catholic, except his central figures are not saints but usually real-life stranglers, cannibals and child murderers, with the circumambient episodes telling their terrible stories.

I have called Coleman an ‘Outsider artist’, knowing he will wince, because that is the convenient, portmanteau term generally used to describe artists who operate outside rather than within the well-mapped territory of the art world, meaning they do not channel art history, reference other artists or play art word-games. Also, they are supposedly self-taught.

A few Outsiderish artists have long been accepted in the mainstream art world, the visionary William Blake being one. (Yes, I know he referenced Michelangelo, there are no rules here.) Another was Henri ‘Le Douanier’ Rousseau, the former customs officer, in whose honour the young Picasso gave a banquet in 1908. It has often been written that Picasso would dismiss the evening as a blague, a prank, and perhaps he did so. But a 1965 photograph of the maestro shows him holding up two canvases he owned, portraits made by Rousseau of himself and his second wife, and there’s no whiff of mockery. Rousseau now hangs in the Louvre and New York’s Metropolitan Museum.

George Widener’s ‘Titanic’ (2007), courtesy Ricco/Maresca Gallery

I should add that two Outsider artists, Alfred Wallis and Scottie Wilson, also received recognition in the UK in the early 20th century. Wallis, a seaman, took up painting aged 67 in 1922, after his wife’s death, but he happened to live in Cornwall, home to the St Ives School, and his work was discovered by Christopher Wood and Ben Nicholson. Wilson, who had fought as a soldier in World War I, began drawing aged 44 in the early Thirties. His work was collected by, among others, two Modernist masters, Picasso — yes, him again — and Jean Dubuffet.

Dubuffet is the more relevant here. Rousseau, Wilson, Wallis are fascinating blips, and not integral to Modern art history, but in 1948 Dubuffet, with André Breton aboard, established a Compagnie de l’Art Brut. This focused attention on the art of the disabled, of schizophrenics in particular. Outsider art as a larger phenomenon was thereby conjured into being, and these emphases — on the self-taught nature of the artist, the art’s connection with disability — have been driving and roiling both the world of Outsider art and its market ever since.

‘I always had difficulty with the phrase “Outsider art”,’ Coleman says. ‘For a long time this so-called Outsider thing was about the story of the artist. He was disabled, or he had shock treatments… which is interesting, but it’s only interesting after the fact. It shouldn’t be what makes it art.’

Tom Duncan, another remarkable artist, is also thus categorised. Does he mind? ‘I don’t,’ Duncan says. ‘Some people call me an Outsider, and some people argue that I am not; I just go along with it. The thing is that I went to art school when I was nineteen and they feel that that pollutes the waters — which I don’t really agree with.’ But he adds: ‘When I first started going to the Outsider fairs I felt like I was having a spiritual awakening. It was just a very deep spiritual feeling that I felt that I wouldn’t feel anywhere else.’

Manhattan’s Outsider Art Fair on West 22nd Street this year showed the genre in all its (often at odds) diversity. There was work by such dark and eccentric visionaries as Aleister Crowley and William Burroughs — yes, that William Burroughs. Three centres that work with the disabled, all based in the Bay Area, were showing art. And the masters were there too — like Henry Darger.

It would be simplistic to say that Darger brought about the remarkable — and ever more rapid — changes in the world of what I have to call Outsider art, but he certainly helped to drive it. It’s a world that has always paid attention to ‘story’ and Darger’s was classic. Born in 1892, he spent his adult life working in menial hospital jobs in Chicago. He died in 1973, and after his death a vastly long manuscript was found in his cheap room, along with sheaves of fantastic illustrations.

Martin Ramirez, born in Mexico in 1895, came to California in 1925. He was hospitalised for schizophrenia six years later and spent his life in institutions, making art on whatever paper he could find, including shopping bags. Some was saved by Tarmo Pasto, a visiting professor in psychology and art. Other troves survived, too. He died in 1963; in 2008 there was a show at New York’s Museum of Folk Art.

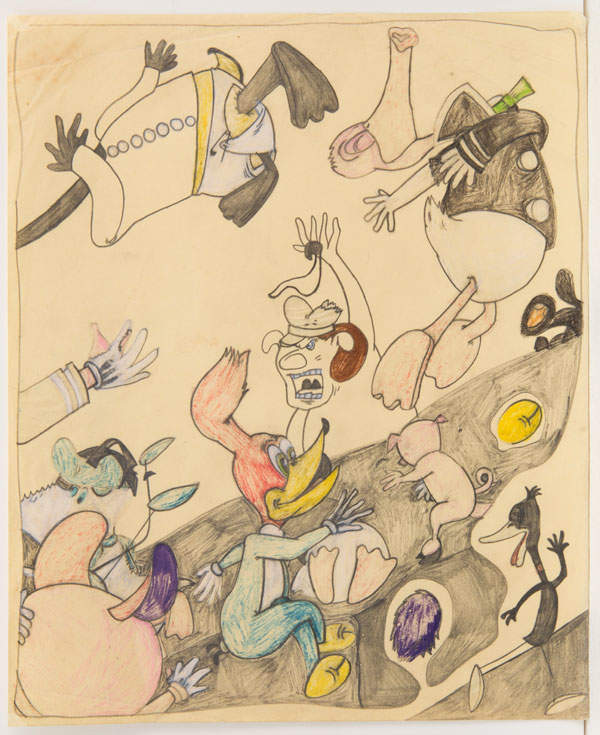

‘Untitled’, Susan Te Kahurangi King (1965), courtesy the artist, Andrew Edlin Gallery and Chris Byrne

These are the heirs to Le Douanier, and like him they are dead. But there are younger artists making waves. Susan Te Kahurangi King is a New Zealander, born in 1951. She too has a classic story, and an odd one. She didn’t speak when we met in the Edlin Gallery, just before her New York show. No surprise — she stopped talking between the ages of four and six and is comfortable with silence. But there’s nothing ‘Outsiderish’ in her work; it’s not obsessive-compulsive mark-making. She makes luminous coloured drawings that mix Pop and abstraction. And her show wowed the city.

The marketplace has, of course, become as never before a part of the judgment process, and another thing of note at the Outsider Art Fair was the prices. In the early Eighties you could have picked up a piece by Bill Traylor for $150; now you can add two or three digits. Drawings by Martin Ramirez were priced in the low six figures. A Henry Darger (not at the fair) recently sold for $750,000. And Susan King? Andrew Edlin, who shows her work at his gallery and owns the Outsider Art Fair, told me that nothing in his show was for sale.

I asked Frank Maresca of Ricco/Maresca, a Manhattan gallery that is one of the most prominent in the genre, just where this renewed attention came from. Maresca talked of going to the Armory Art Fair and wandering around the subsidiary fairs.

‘With regard to the Contemporary arena there wasn’t an awful lot that got me excited,’ he said. ‘I have to tell you that. It seemed like art was being produced or stamped out in a way that was popular, whatever was bringing the big money in the Contemporary marketplace; lots of people seemed to be jumping on that bandwagon and producing art that was in some way similar or related to it. I’ve not seen a lot, certainly within the last ten years, seven years, five years, that’s getting me excited. I walked through all those fairs, hoping to get goose bumps and have hair on the back of my neck stand up, and it just didn’t happen. Most of the time I was yawning.’

But of Outsider art, Maresca says: ‘It just seems to be fresher. It doesn’t owe anything to anyone, and it’s not connected to the whole commercialisation of the art market. It has an independence, it has a freedom, it has a freshness, it has a raw quality, it has a truth to it. I think that’s probably the bottom line.’

Well, as the late Mandy Rice-Davies said in a wholly different context, Maresca would say that, wouldn’t he? That’s the work he deals in. But dealers are also moving in from the Contemporary mainstream. David Zwirner’s last show at his New York gallery was of Outsider art. And such influential curators as Lynne Cooke of the National Gallery in Washington DC and Massimiliano Gioni of New York’s New Museum have long been there, as has Matthew Higgs of the Manhattan non-profit White Columns.

Maresca’s use of such language as freshness, rawness and truth seems to the point. Most professional artists sometimes make product — and not just hacks. Picasso made some product, Warhol made tons of it. But Outsider artists? I think a good definition of authentic Outsiders is that each piece is a one-and-only. ‘If I’m doing a painting, I don’t have any sketch,’ Joe Coleman says. ‘I’m working on a square inch at a time, and not knowing what the whole image is going to be, how the whole thing is going to come together. Every painting I make is like a matter of life and death for me.’

But just when I’m thinking I’ve got a working definition, I realise everything was probably a one-off for Giacometti, too. Also Bacon, Jackson Pollock, the list could go on. That’s what keeps you at it in the art world, it’s a game with no fixed rules. But I’ll end with a premonition, which is that this Outsider phenomenon has just got going.