The House of Mondavi: The Rise and Fall of an American Wine Dynasty

Julia Flynn Siler

Gotham Books

Robert Mondavi, who passed away on May 16 2008, invented the modern American wine industry. His technical improvements and marketing strategies brought worldwide recognition to the wines of California’s Napa Valley. In 1965, when Mondavi set up his winery in Napa, Americans generally drank their wines sweet and from a jug. The post-prohibition wine industry turned out rot-gut wines in gallon flagons, much of it aimed at the ‘wino’ market, for which alcoholic kick was far more important than oenological sophistication.

To a great degree, Mondavi changed all that. His ambition was to make drinking wine a part of everyday American life, a mealtime accompaniment for the working man, just as it was in southern Italy, from where his father, Cesare, and his mother, Rosa, had emigrated to the United States in 1908. He successfully developed a number of well-respected premium wines, including the Robert Mondavi Reserve, which in the 1970s was on almost every list of top-ten Napa reds, as well as launching the Mondavi Woodbridge Winery in Lodi, California, developing it into a leader in the popular-premium-wine sector.

Mondavi certainly improved the image of Californian wine, starting with the French, who once sneered that US wines were for cooking, not drinking. Whether he made drinking wine into an everyday experience for his countrymen is another matter. ‘Chardonnay sipping’, like ‘latte drinking’, is shorthand in the US for ‘liberal elitist’. Real Americans still drink beer.

Part of Mondavi’s marketing strategy was to demystify wine. He was an aggressive proponent of labelling wines varietally – identifying them by the grapes from which the wines are made. He soon discovered that consumers like varietal wines: it reduces the options that need to be sifted – the provenance, the year, the winemaker – to one: the grape variety. Potential customers who might be put off having to order a 2004 Chateau Whatsits Burgundy, could comfortably ask for ‘a Chardonnay’. Varietal labelling has now become the norm for New World wines and, increasingly, for lower-end European wines.

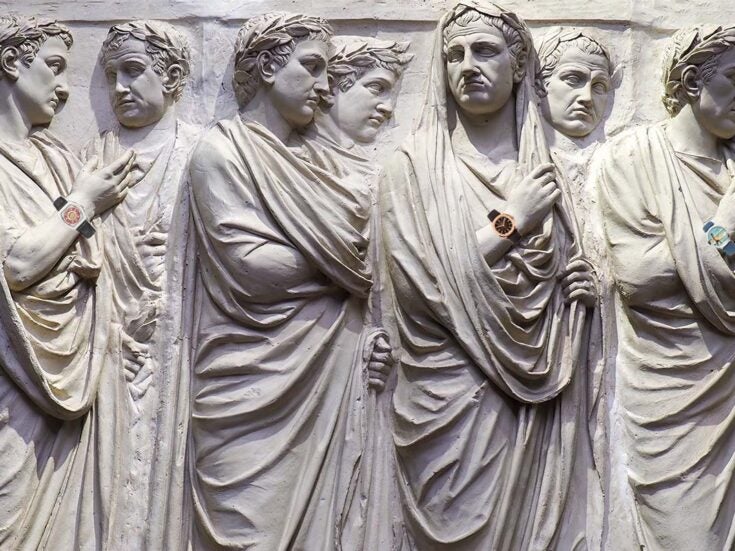

Not everyone is happy with this. In the traditional Old World wine industry, such marketing strategies are seen as dumbing down consumer choice. The traditionalists believe that soil – the terroir or ‘land’ – and climate are the chief determining factors of a wine’s quality. Known by their opponents (rather wittily) as ‘terroirists’, they refer to the modern varietals as ‘international’, a polite way of saying ‘big, fruity stuff without any character’.

The House of Mondavi says very little about how Robert Mondavi revolutionised the wine market. She seems, in fact, to be quite uninterested in the subject of wine altogether – either in the making or the selling of it. Instead, she focuses on the damily saga, which she sees as a Greek tragedy of ‘greed, mismanagement and conflict’ that tore the family apart and led, eventually, to the sale of the winery to an outsider.

The story starts with Cesare and Rosa, who moved to Napa in 1923 and eventually bought the derelict Charles Krug winery, renewing its reputation for quality wines after the end of Prohibition. Cesare’s hope was that his two sons, Peter and Robert, would combine their talents and work together to create a lasting wine dynasty. Fat chance. Their differing philosophies and personal animosities developed into a decades-long feud, and to Robert’s eventual dismissal from the business.

Cesare was dead by the time of Robert’s ousting, but his mother Rosa supported the move. In effect, she chose one brother over the other. Robert’s response to this maternal rejection was to launch the Robert Mondavi Winery, in competition with Charles Krug.

The Mondavi Winery easily surpassed Charles Krug, both in reputation and market share, which may, Siler suggests, have been Robert’s intention – as if to prove to his mother that she had backed the wrong brother. Robert’s ultimate ambition was the same as his father’s: to pass on a family wine business to his two sons, Michael and Timothy. Rather predictably, Michael and Timothy continued the Mondavi tradition of sibling rivalry, squabbling about everything from the direction of the company to what

sort of wines to make. Robert’s ill-considered solution was to let his sons share the CEO title, against the advice of just about everyone, thus ensuring that the squabbles would continue at board level.

In 1993, the company went public, enabling its investors, chiefly the Mondavi family, to prosper when the stock went up. On paper, they made millions. Robert chose to use his new wealth to become a philanthropist, committing much of his stock to a Napa Valley cultural centre he had founded and to the University of California at Davis. When the stock went down, Robert’s charitable pledges threatened to bankrupt him. The eventual solution was the sale of Robert Mondavi Winery to a faceless, New York-based conglomerate called Constellation Brands Inc.

Julia Flynn Siler tells this story in a style that veers between Hello magazine and Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous. She ignores what could be interesting – how the business was run; how it made its wines; how it succeeded – and instead puffs out the narrative with inconsequential details, such as what the bridesmaids wore at Michael Mondavi’s wedding. This is much more a celebrity biography than a proper business book.

Still, as an explanation of how not to do succession planning, The House of Mondavi has its moments. Ultimately, it was the Robert Mondavi Winery that the family lost. Charles Krug is now run by Peter Mondavi’s childen. Perhaps in the end Rosa backed the right brother after all. says very little about how Robert Mondavi revolutionised the wine market. She seems, in fact, to be quite uninterested in the subject of wine altogether – either in the making or the selling of it. Instead she focuses on the family saga, which she sees as a Greek tragedy of ‘greed, mismanagement and conflict’ that tore the family apart and led, eventually, to the sale of the winery to an outsider.

Review by Paul Mungo