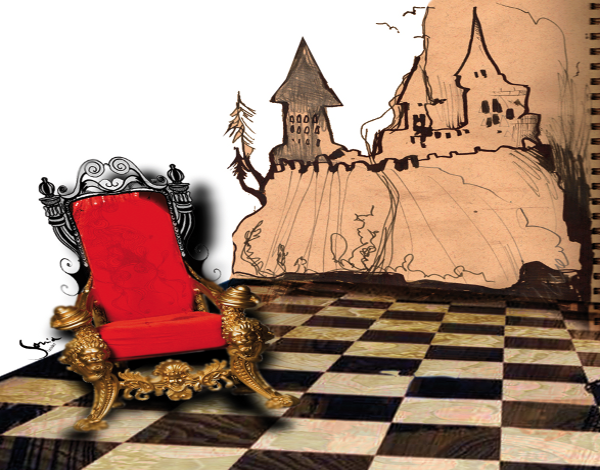

Throne Out

What happens to the children of deposed royal dynasties? Sophie McBain finds out

‘WHAT’S THE SENSE of a royal family nowadays, when it’s lost political power?’ muses Philipp von Habsburg, whose great-uncle Karl was the last emperor of Austro-Hungary and whose family ruled swathes of Europe and beyond for over 650 years. ‘It’s to represent certain values and traditions, and to live those in daily life.’

When the Habsburg monarchy was deposed in 1918, the family was left with little but a name that shut more doors than it opened and a rich, complex and abruptly interrupted history of imperial power stretching back to the 13th century. ‘Our family was thrown out of Austria without anything, literally a suitcase,’ says Philipp, a founding partner and CEO of London-based Trinity Capital Partners, which raises money for hedge funds. Philipp’s father, Archduke Heinrich, stopped using the Habsburg name for fear of his safety and began his career as a worker on a sawmill before becoming a successful businessman. But despite outward appearances, Heinrich took great efforts to ensure that his children were raised on the stories and traditions of his influential forebears.

It is an upbringing that Kyril Saxe-Coburg, managing director of client advisory at Man Group and a Princeton-educated physicist, can relate to. Kyril’s father, King Simeon II, was crowned King of Bulgaria in 1943, when he was only six years old. The monarchy was overthrown the following year, and shortly after King Simeon II’s ninth birthday, the family was exiled.

Despite having a fairly ordinary childhood in Spain (‘We were brought up in a very low-key, normal environment, completely anonymous,’ Kyril says), they too were instilled with a strong sense of duty to uphold the family name. ‘There was always a historical responsibility,’ he explains. ‘We were brought up to be aware that we represent part of the history of the Bulgarian nation, and as such that we should behave in a certain way. But it was an obligation, there were no rights attached.’

There was little chance of forgetting Bulgarian roots in the Saxe-Coburgs’ Madrid family home. The house was always filled with fellow Bulgarian exiles, the cook prepared Bulgarian food and the walls were hung with Bulgarian pictures. ‘We’d wear Bulgarian costume at school,’ he says.

Kyril is quick to point out the humorous sides of his upbringing. Their Madrid home was a ‘microcosm of Bulgaria’ but was forever frozen in the pre-war period. Bulgarians are still amused by his father’s antiquated accent, ‘because he sounds like a BBC news broadcaster from the Second World War’. And a side-effect of being able to trace your family roots to the 5th century, he jokes, is that on planes he regularly realises he’s sitting next to a reasonably close relative who has no idea of the connection.

Kyril’s royal heritage has, however, always had more serious implications. The communist government might have hoped to erase the history that King Simeon II lovingly preserved at home, but it was equally obsessed with it. When the Bulgarian regime began striking out at dissidents abroad, Simeon II pressed upon his offspring the need for caution when they left the house. His worries were not unfounded: when the communist security service’s files were released, it was revealed that the house had been under surveillance.

Republican governments’ paranoia when it comes to deposed monarchies can be surprisingly enduring, Philipp has discovered. As late as 1996, his relatives were not allowed to travel to Austria unless they renounced their titles first. The government’s stubbornness was matched only by two of Philipp’s octogenarian uncles, who took advantage of Austria’s open borders following EU accession to smuggle themselves into Vienna and call a press conference, forcing the government to reassess its policy.

Illustrations by Sonia Hensler

ALIA AL-SENUSSI, an executive at Generation Three Family Partners, also spent a childhood in exile and under the radar of a history-obsessed republican government. Her father is Prince Idris al-Senussi and her grandfather, Prince Abdullah Abed Al-Senussi, was a cousin, brother-in-law and close aide of former Libyan monarch King Idris.

Prince Idris was once blacklisted by the Gaddafi regime, but Alia, who spent most of the year living with her mother in the US, says she was too young to understand the significance of the protection officers sometimes positioned outside her father’s London home. While her father’s household was steeped in ‘nostalgia’, Alia lived in an ‘idyllic Californian neighbourhood’ with her mother, and later studied at Brown University and the LSE. Libya seemed very distant, and with Gaddafi showing few signs of losing his grip on power she never believed she would one day return to her home country.

As a result, she was taken aback by her reaction to the revolution: ‘I felt very personally connected to it, so my immediate reaction surprised me. Because I feel very Libyan, but it’s almost an ephemeral way of being Libyan, because I’ve never been there, I don’t live in a Libyan community and even most of the Arabs I know are not Libyan.’

Alia’s first instinct was to call the Red Cross to help with fundraising, and she has been working with her family charity, the Senussiya Foundation, to provide humanitarian assistance. ‘I think my family all feel we have a responsibility, but I don’t think that’s anything to do with being from an exiled royal family. I think it’s something everyone in the diaspora feels,’ she says.

Alia, Kyril and Philipp share a feeling of responsibility towards the countries their family once ruled. Kyril stepped in to work as an economic adviser to the Bulgarian government in the late Nineties, and Philipp feels he ‘really should’ go into politics, but a disillusionment with the mainstream Austrian parties has held him back.

The trend is more pronounced among the older generations. Prince Idris has publicly declared his support for the revolution and his desire to return to Libya. In 2001, King Simeon II became one of the few hereditary monarchs to later be elected to power when he became prime minister of Bulgaria. ‘My father is not really a political animal at all,’ says Kyril, ‘but for him it was like going full circle, going back to his country and making a difference, although in this case as a prime minister rather than a hereditary king. He didn’t care one way or another, as long as he can do something for his country — that’s all he cares about.’

Similarly, Philipp’s uncle, the late heir to the Habsburg throne, Otto von Habsburg, ‘loved politics, almost excessively’, Philipp says, and he devoted his life to promoting European integration. In a moving homily at Otto’s funeral, Cardinal Christoph Schönborn suggested that Otto was in part motivated by a sense of responsibility for his family’s unwitting involvement in the events leading to the First World War. Philipp believes there could be some truth to the theory.

When diplomats at the Bulgarian embassy in London began clearing their office of communist memorabilia, they discovered some old paintings of King Boris III (King Simeon II’s predecessor) hidden behind the modern portraits. It’s not fashionable to believe that power, privilege or wealth should be inherited, or that a name should shape your life-choices. But the heirs to deposed royal families understand that no matter how determinedly their ancestors’ legacy is concealed, it cannot be erased or escaped. History always resurfaces, in one way or another.