It’s in Cambridge, but not of Cambridge. Or is it of Cambridge but not in Cambridge? The Hauser Forum, ‘a focal point for entrepreneurship’, sits outside the main university’s realm in the West Cambridge Research and Development Park. But it does belong to the University of Cambridge, as the ubiquitous logos attest, and it has academics working there. Then again, it also houses private enterprises in both start-up and established stages.

It is no small wonder the place invites confusion. The Hauser Forum — named after entrepreneur-benefactor Hermann Hauser, who set up early computer company Acorn — forges a connection between academia, research, business and finance. As such, it belongs both to the university and to business. It is designed to encourage creative collisions, or in the words of the University of Cambridge, ‘stimulate innovative collaboration between clusters of academics, start-ups and established businesses’. ‘Cluster’ is the magic word.

The UK’s science and technology clusters have grown into thriving hubs and are significant contributors to the UK’s economy. The Cambridge cluster, for instance, has 1,500 firms and 54,000 employees, and produces over £12 billion of revenue a year. The newest addition is the £330 million AstraZeneca research and development site due to open on the Cambridge Biomedical Campus in 2016, as the pharma giant prepares to move its operations there.

Another major sci-tech cluster, in Oxford, has 1,500 hi-tech firms and 43,000 employees. ‘Our biggest sector is bioscience, followed by IT,’ says Ian Macpherson, business development manager of Oxford Business Park. ‘But we also have our slightly smaller cryogenics and space engineering sectors, which mark us out as different from the other parks.’

Thrice blessed

Down the M40, East London’s Tech City (aka Silicon Roundabout) is said to be the third-largest technology start-up cluster in the world, after San Francisco and New York. It differs from Oxford and Cambridge as it comprises largely consumer IT companies such as Google and Facebook, rather than the more specialised B2B scientific start-ups. The Crick Institute, due to open next year in King’s Cross, will specialise in biomedical research, adding a new dimension to the cluster.

Spotting an opportunity for London and the UK within the healthcare sector, Boris Johnson is seeking to interlink the three key sci-tech cluster cities — dubbed the golden triangle — through the new MedCity scheme. This partnership aims to establish London and the greater South East as a world-leading cluster for life sciences.

Each of these communities has already thrived largely thanks to the clustering effect: these cheek-by-jowl businesses facilitate intricate networks and stimulate innovation through the cross-pollination of ideas and expertise. ‘There is such a diversity in experience and background within our group, but we support each other and collaborate,’ says Struan McDougall, chief executive of private business angel company Cambridge Capital Group.

Entrepreneurs also benefit from a certain job security through this supportive network: if their business fails they are able to tag themselves on to another venture. In clusters, people are sticky, but ideas are not.

At an event in June at the Royal Society in London, Cambridge-based organisation Silicon Valley Comes to the UK (SVC2UK) stressed how important bioscience and healthcare technologies, the specialist areas of the UK’s clusters, are for the UK’s welfare and economy. Sherry Coutu, an angel investor and founder of SVC2UK, which brings together entrepreneurs and investors from Silicon Valley and the UK, discussed why private investment is crucial for the development of these sectors. Traditional funding options like venture capital, she said, are often not available to science businesses largely because there is often a long turnaround time on investment.

There is also exposure to risk. ‘There are many layers of risk in setting up or investing in a science tech start-up, ranging from the technical risk to the manufacturing, marketing and sales aspects, plus scalability and the quality of the team,’ says George Whitehead, venture partner manager at Octopus Investments, which specialises in investing in smaller companies.

Despite the drawbacks, there are plenty of opportunities to make money, according to the panel at the SVC2UK event, which included Hermann Hauser, Robin Saxby, founder of Cambridge-based multi-billion-pound ARM Holdings, and Andy Richards, founder and special adviser to Vectura Plc, who produced the Cambridge cluster’s tagline, ‘Cambridge has become a low-risk environment to do high-risk things in.’

Expanding on the opportunities, Coutu said: ‘The diagnostic-to-treatment percentage in healthcare stands at 30:70 currently,’ meaning much more money is spent on the latter, ‘but is set to go to 50:50. That’s a 20 per cent change in the market worth trillions of dollars. There will be business opportunities in things like healthcare apps or data machines.’

Niche market

The majority of companies within the Oxford and Cambridge clusters are business-to-business operations and are thus not as well known by the public as business-to-consumer companies such as Google or Facebook. This, combined with the specialised and often complex nature of many of the businesses, means that while funding is much needed and encouraged, investing in science and technology enterprises is not always straightforward.

There to help investors monopolise on the plentiful opportunities within the sci-tech clusters are angel investor organisations such as Cambridge Capital Group or Oxford Investment Opportunity Network (OION). Since, as Struan McDougall of the Cambridge Capital Group points out, new members usually come through existing contacts, it might be worth ransacking your address book to see if any of your acquaintances have already invested.

For those with less involvement in the sector, companies such as Octopus facilitate investments in the sci-tech arena. ‘We deal directly with entrepreneurs from this sector who are looking for funding or advice,’ says Whitehead. ‘Sometimes we come into a venture in the seed round and co-invest with other angels, other times angels introduce us to ventures in the second round of investing. We also run our own angel investment organisation.’ Amadeus is another company which lets HNWs invest in sci-tech start-ups.

As with the entrepreneurs, investors also benefit from the close-knit, supportive cluster environments when making funding decisions. ‘Investors receive expert advice and due diligence not just on one company but on all of the businesses within the cluster,’ said Hermann Hauser at the SVC2UK event. An example of this type of expert consultancy provider is Alacrita, which has offices in London and the Cambridge Science Park.

Oxbridge notes

One thing supporting the success of Cambridge and Oxford’s clusters is their unique city infrastructures, which include the country’s top universities who are producing a flow of talent; world-class hospitals; and research facilities close to each other. ‘There is usually one degree of separation from anyone of influence,’ says McDougall.

Oxford and Cambridge both benefit from the close-knit environment of smaller cities. However, should the two clusters continue to expand, neither city currently has the public transport network in place to ensure the maximum interconnectedness that London enjoys. To combat expansion issues, Cambridge is planning to build a new railway station by the science park, plus a direct bus link and improved foot and cycle ways, while in Oxford the government is funding road and public transport links to the business park.

But while London may have a more sophisticated transport infrastructure, its sheer size means it is difficult to create an intimate networking environment akin to Oxford and Cambridge. ‘The problem with London is it’s too big and overdeveloped so it’s not usually possible to build hospitals, research centres, universities, start-ups and investment companies in a concentrated area,’ says Charles Cotton, founder and chairman of Cambridge Phenomenon Ltd, which aims to acknowledge the people and organisations behind the Cambridge cluster. ‘For instance, in Shoreditch the start-up warehouses around Tech City are now being turned into luxury flats.’

Creating interest around the clusters helps generate much-needed funds; fetishising them is ill-advised. ‘Tech City did much better before everyone started talking about it,’ says Bradley Hardiman, an investment manager at Cambridge Enterprise. ‘It tried too hard and then collapsed under its own weight.’ So when it comes to hi-tech, perhaps it’s best to stay low-key.

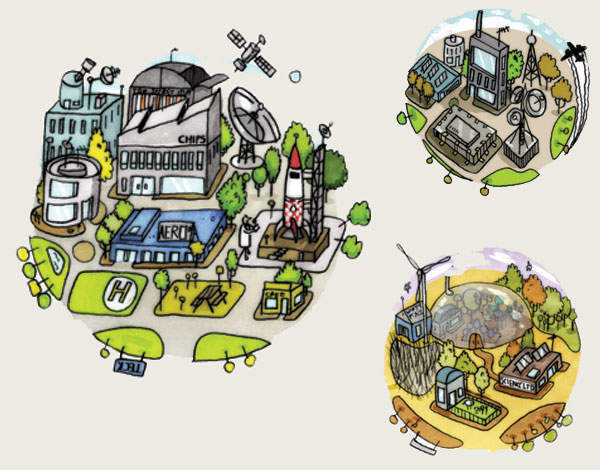

Illustration by Rich Gemmell